For the past five years, producer D’Mile has been on a hot streak. In 2021, he won a song of the year Grammy for his work on H.E.R.’s “I Can’t Breathe.” Shortly after, her “Fight for You” (from the film Judas and the Black Messiah) won D’Mile and H.E.R. the Academy Award for best original song. Then, in 2022, he became the first songwriter to score back-to-back song of the year Grammy wins when Silk Sonic’s “Leave the Door Open” took home the prize. And now, he could potentially claim that same landmark award again: He’s nominated for it at this year’s Grammys for his collaboration with Bruno Mars and Lady Gaga on the retro power ballad “Die With a Smile” — one of three nods he received, in addition to producer of the year, non-classical and best engineered album, non-classical (for Lucky Daye’s Algorithm).

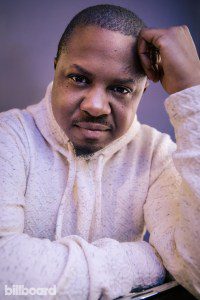

But for the artist born Dernst Emile II — who, at 40, has now accumulated 20 career Grammy nominations — what may seem like overnight success actually took nearly two decades.

Trending on Billboard

His entry into the music industry was in many ways charmed. His late mother, Yanick Étienne, was a singer who toured with Bryan Ferry and Roxy Music, while his namesake father still works as a music producer and teacher. D’Mile himself joined the business at 19 and notched his first production credits in 2005 on projects by Rihanna and Mary J. Blige, before pop-R&B heavyweight Rodney “Darkchild” Jerkins (Destiny’s Child, SZA) took him under his wing as a mentor. In the years that followed, D’Mile logged songwriting and production credits for Janet Jackson, Justin Bieber and Usher, among others.

But for D’Mile, “chasing what was hot to get on projects” during those early days wasn’t satisfying. “I was slaving away making five to 10 tracks a day,” he recalls today, sitting in the cozy reception room in his Burbank, Calif., studio. “But things weren’t moving at the pace I would have liked.”

In 2008, he decided to take a mental break and recalibrate. He amicably ended his publishing agreement with Jerkins and made a pledge to himself: to do “what I love, and if it goes anywhere or doesn’t, it’s something I’m proud of.” Lo and behold, things started falling into place that had seemed elusive — like getting more opportunities to work directly with artists instead of “guessing and throwing spaghetti against the wall” when pitching songs. In turn, D’Mile was able to foster long-term relationships with future Grammy winners like Victoria Monét and Daye.

Despite that positive momentum, D’Mile still considered quitting around eight years ago, after “reaching a point of frustration” with industry politics. “It seemed like it was more of a popularity contest or knowing the right people to get in certain rooms or positions that I’d worked so long for,” he says. “I just felt like things weren’t progressing.” He posted his feelings on Instagram Stories, which elicited supportive comments from friends and colleagues telling him that he couldn’t give up.

That’s where Daye came in. Then only a songwriter, he told D’Mile that he wanted to become an artist in his own right — and to bring D’Mile on for a project. “Doing what we wanted to do was a life-saving kind of project for me,” D’Mile recalls of producing and co-writing what became Daye’s 2019 debut album, Painted, which then went on to receive a Grammy nod for best R&B album. “That was the battery in the back that I needed,” he says. In 2022, Daye’s Table for Two, which D’Mile executive-produced, won the Grammy for best progressive R&B album; now, the singer’s third studio set with D’Mile, Algorithm, is vying for best R&B album (which could give D’Mile another Grammy if Daye wins) and best engineered album, non-classical.

Joel Barhamand

What role have your Grammy wins played in your career thus far?

It’s funny. Every time Grammy season comes around, I’m always nervous. I’m so grateful to have the wins, but then I’m like, “One day, that’s going to stop.” With these new nominations, I’m happy that people still like what I do. The attention you receive is something I had to get used to, especially the first time, because I’m kind of a quiet guy. My phone was blowing up and I had to do interviews. It was crazy. But I also feel it has made things easier because a lot of people are coming to me more than I’m trying to get to them, which is great. Yet navigating that can also be overwhelming.

What do you feel is the secret behind your success as a songwriter and producer?

I always just try to bring out who the artist is by getting to know them. It could be a conversation that sparks something before we start or while we’re working together. Or I’ll hear a conversation between the artist and another songwriter, and I’m feeling the vibe, feeling them both out. I like to say that I don’t talk; I listen. And when I create, it’s like my interpretation of who the artist is.

You’re in strong company in the producer of the year, non-classical category this year. Is there more camaraderie among producers now compared with when you were coming up?

Growing up in this business, and being with Rodney, I feel like it was way more competitive back then. And maybe some people might feel that’s better, but it can be negative to be so competitive. I’ve heard horror stories about what people can do just to get something over somebody else. For me, even though I’m up against you, we could probably work together tomorrow — so let’s do something great together. I don’t think that was happening as much back in the day.

I’ve worked before with Mustard. And Dan Nigro and I always talk. I’m such a big fan of his and what he’s done with Chappell Roan and Olivia Rodrigo. I met Alissia a few years ago; it’s great that a female has been nominated. I know a lot of people might not know her, but she’s super-talented. I haven’t met Ian Fitchuk yet but I have heard his work. I learned that he’s a fan of me as well, and that’s cool.

What kind of change would you like to see the industry as a whole embrace?

Streaming is the biggest way that people are listening to music, but it’s not translating that way for songwriters and producers. We’ve just got to make it make sense. That’s the main thing as far as income is concerned. I’ve donated to small companies that are fighting for that, like the organization a friend of mine, Tiffany Red, founded called The 100 Percenters. It advocates for the rights of songwriters and producers. I want to get more involved in that fight for sure.

Given the hot catalog-sales climate, have you been approached about selling yours?

People have talked to me, but it’s never gone as far as “I want to do a deal with you.” I guess it’s situational. Yet in the grand scheme of things, why would you do that? But I don’t know… I’m still learning about all of it at this point.

As one of today’s principal architects of R&B, what’s your take on the state of the genre in 2025?

The most important thing is really caring about the song that you’re writing as an R&B artist. There’s a lot of great stuff happening, but sometimes I feel like some R&B songs topicwise only cater to a certain demographic of people. It’s about finding the balance in keeping the integrity of R&B/soul while making it so that all walks of life can relate. Toxic R&B, that’s a Black thing, and I don’t know how much many other people in the world relate to that. So I think it’s important to make a great song but leave it open a little more for interpretation. We just need to make songs that connect with more people. Then if the songs are more open, it will cause a domino effect. I would like to think that there isn’t really a wall for us not to get bigger than we can be. We’ve just got to be more intentional and not comfortable with where we are. That will change the game, because the industry just follows what’s making the most money. And I feel there’s a world where R&B will be that.

This story appears in the Jan. 25, 2025, issue of Billboard.